I will start off this post by saying that this cadence was not invented nor first used in Mario, however, it is found all throughout the music of Koji Kondo and others who were inspired by his music.

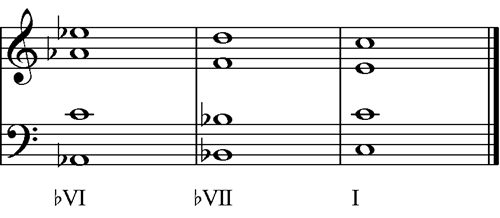

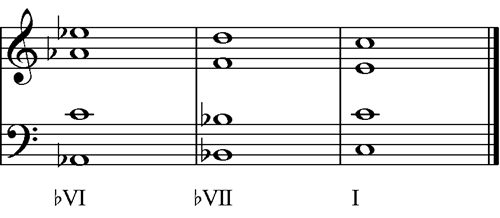

The cadence in question, is the one pictured above. The motion of bVI-bVII-I. The example above is given in C major with rather arbitrary voice leading. For those of you who have memorized all your part-writing rules, you will notice this progression is nearly impossible to write without violating a convention or two (when writing in four parts). You will notice from all the examples below, ascending parallel 5ths and Octaves are very common when writing out this progression.

In my master’s thesis, I briefly discussed the use of modally inflected harmonies used as substitutions for more traditional harmonies. The following paragraphs are taken from that thesis,

Examining Non-Linear Forms: Techniques for the Analysis of Scores Found in Video Games (Texas Tech University, 2009):

Walter Everett’s discussion of tonal systems in Rock music provides a great explication of the use of modal inflection in the language of popular music. He discusses six different tonal systems that he believes are prominent in the tonal systems of Rock music. The system that is dominant with the composers discussed here is his third system: “Major-mode systems, or modal systems, with mixture from modal scale degrees. Common-practice harmonic and voice-leading behaviors would be common but not necessary.”[1] This system allows for the substitution of chords from modally inflected scale degrees to function as their diatonic counterparts would.

For example, the music of the composers examined below frequently employ the aeolian bVII chord functioning as a substitute for a more traditional dominant chord, such as V or vii°. The bVII can be heard as a dominant chord because it retains the motion from scale degree four to scale degree three in a bVII-I progression. This is the same voice leading motion that governs the voice leading in the V7-I motion. The bVII removes the leading tone, but creates momentum through other voice leading tendencies.

We see the bVI lead often to the bVII in cadential motion. Björnberg acknowledges this cadential motion as frequently "replacing the iv-V-i cadence of ‘regular’ tonal minor.”[2] We see it often replace the IV-V-I cadence of “regular” tonal major as well. Not only that, but we also see an example of bVI alternating with I. Both of these are normal functions of a vi chord: substitution for the IV chord in a predominant function, as well as the expansion of a tonic area. The bVI makes a good substitute for vi because it retains the tonic pitch and interval relationship in size (though not quality). Its third relationship to tonic allows it to continue to function as a tonic embellishment. It functions in the cadence because it allows for a descending third progression from the lowered third scale degree. These modal chords retain the function of their diatonic counterparts, and can be understood as functioning like those chords, even though some of the voice leading conventions are removed or altered.

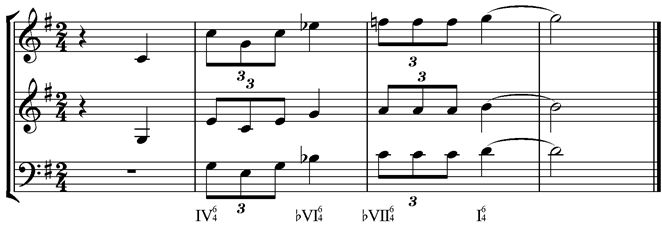

The most well-known example of this cadence in video game music is found in the Overworld Object to

Super Mario Bros., hence the moniker “Mario” Cadence:

This particular cadence is used also in the fanfare for the end of each level:

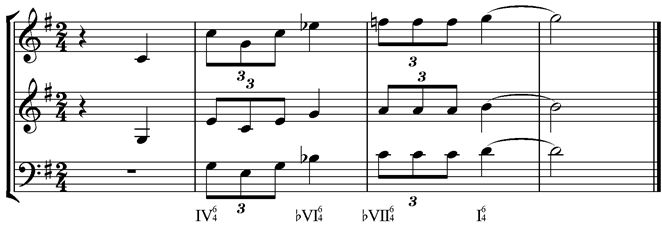

In the last post, I showed this example of the cadence in

Super Mario Bros. 2:

Used as a common device for fanfares in the Mario series, we now see it used in

Super Mario Bros. 3 Airship Victory Fanfare:

This harmonic language was not restricted to the Mario games from the NES era, as we can hear in the Dire, Dire Docks object from

Super Mario Bros. 64:

Harmonic Progression: I | bVII | I | bVII | bVI | bVII | I

In fact, much of the A section of this object follows that progression. When the bVI enters into the progression, the sense of cadence, or at least tonal center, becomes solidified.

Finding this cadence all throughout this music makes us wonder about its power and how it works. It lacks a clear leading tone and dominant/tonic relationship, yet it draws our ears towards tonic in a way that no classical cadence does.

Cruise Elroy posted on this cadence back in 2008, which can be viewed

here. He does an analysis of three

Ocarina songs from

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which have this cadence in them, and also shows us an example of this cadence in

Super Mario Galaxy.

For now, this progression will be coined the “Mario Cadence” and will be identified as such until better nomenclature is developed or found.

[1] Walter Everett, “Making Sense of Rock’s Tonal Systems,”

Music Theory Online Vol. 10, No. 4 (December 2004), http://mto.societymusictheory.org/issues/mto.04.10.4/mto.04.10.4.w_everett.html.

[2] Alf Björnberg, “On Aeolian Harmony in Contemporary Popular Music,” Typescript,

http://www.tagg.org/others/bjbgeol.html.