For those who have been following my articles, you know that most of the groundwork for my posts originated on my graduate thesis Examining Non-Linear Forms: Techniques for the Analysis of Scores Used in Video Games. I want to explore an under-developed topic from that work, and that is the concept of form within a video game score.

My primary interest in game music analysis is “big picture” analysis: how do you examine the entire game music score and all its objects to make sense of it, and how does it help to inform other aspects of ludology. I utilize game score graphs to visualize all the objects in a game or section of a game, and help to inform analysis of relationships and the score as a whole.

In doing these graphs, there are a couple of “forms” that begin to emerge. These forms mirror the format of the games themselves, though sometimes these forms are not as obvious as the game design itself. The first is Linear. Before I dive to far in, I want to say that game scores are rarely just one type or the other, but usually some sort of combination of different styles.

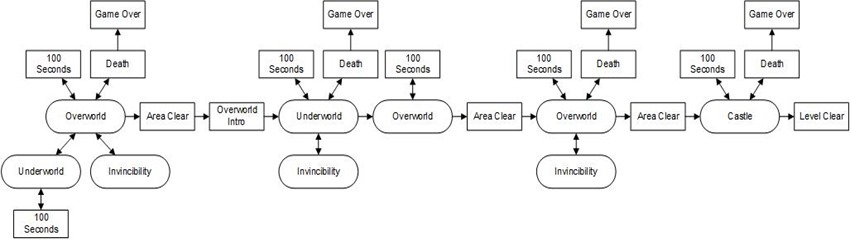

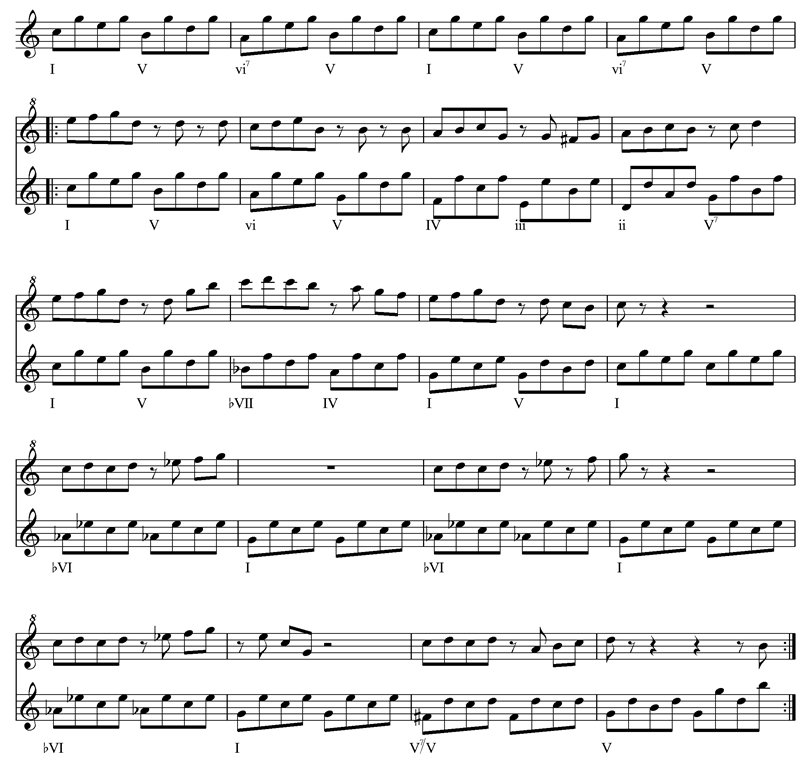

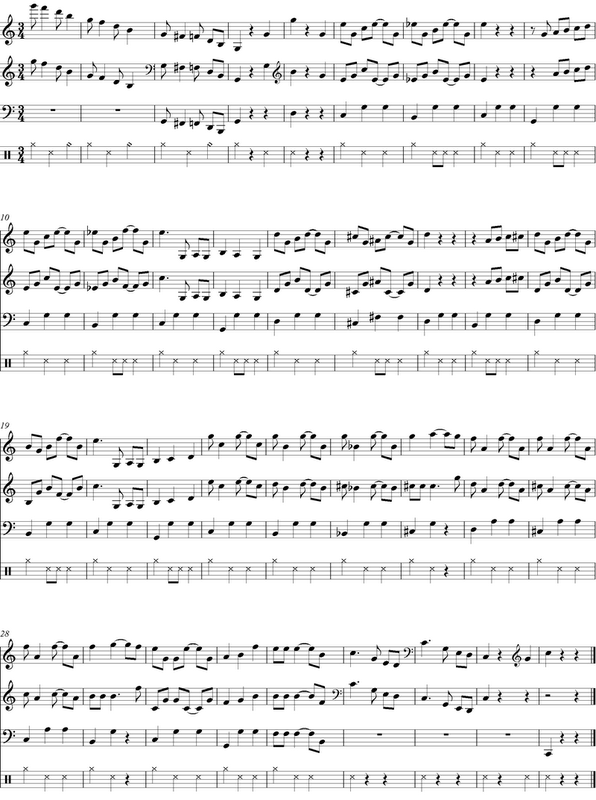

In a Linear game score form, the player is forced to experience the game music objects in a set order. When the game score has a strong linear component, the composer has a much larger control over the musical direction of the objects and game itself. One of the clearest, simplest example to look at is the original Super Mario Bros. We will examine the entire Real Time Game Score Graph (RTGSG) of World 1 as we explore the linear form:

(Click to zoom.)

For those who have not seen these graphs before, rounded objects are objects that loop, while squared objects are of a definite length. Using Schenkerian terms, this is a very surface level look at the game score graph, as we are displaying each and every object.

When looking at an RTGSG, you can identify linear structures as structures that continue to move forward through various objects. There is no central object that stands out as being the single return point. One might argue that the “Overworld” object in this game is one such object, but if you look at the place and function of it, it holds the same weight per instance as the Underworld or Castle object as the predominant object for a section of the game. The structure of the game, and therefore these objects, put us on a continuous fixed path throughout the game that gives this RTGSG a predominantly linear structure.

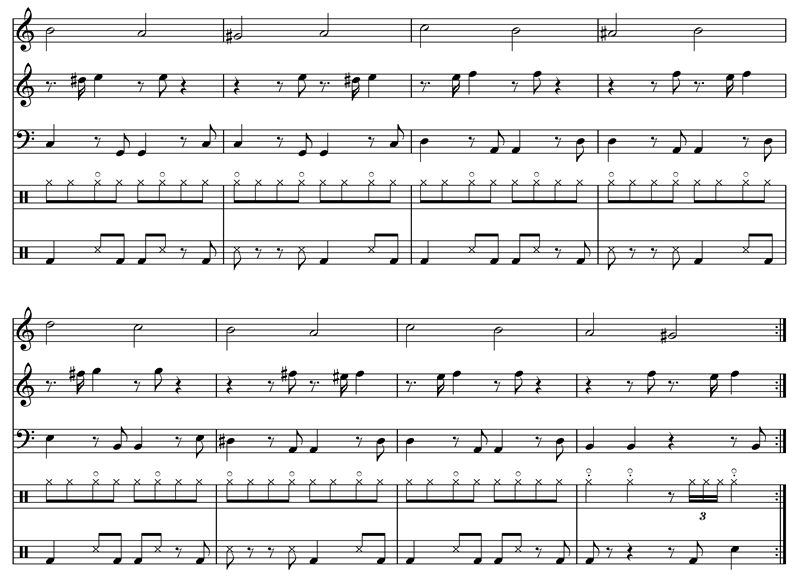

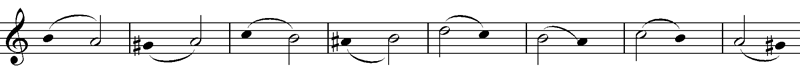

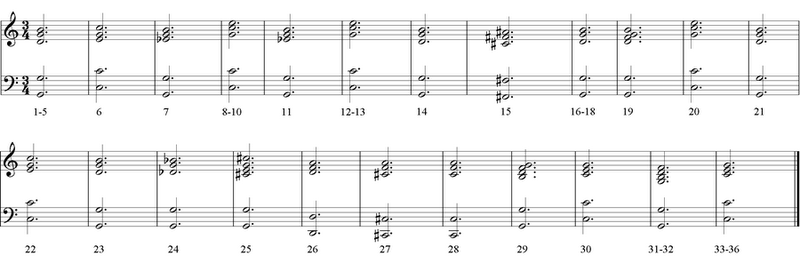

It will be more obvious if we reduce this RTGSG down to a more middle ground texture. Borrowing concepts and techniques from Schenker, many of these objects can be reduced out of the surface level to give us a deeper structure of this game score:

Just as you would reduce out embellishment tones in a middle-ground schenker graph, these objects that interject within other objects can be reduced out as well. Now the linear texture is much more obvious.

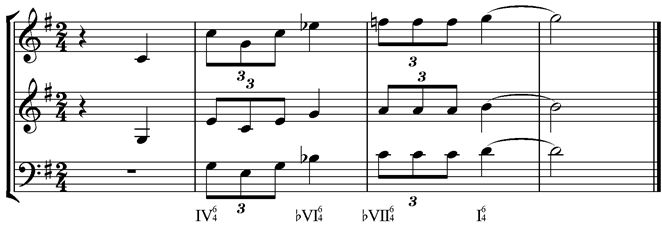

When looking to analyze larger sections of game scores, one technique is to identify what type of form the game score has. That will inform the best way to approach a large scale analysis. Now that we have gotten a core linear structure of Super Mario Bros: World 1, we can examine each individual object and its tonal center.

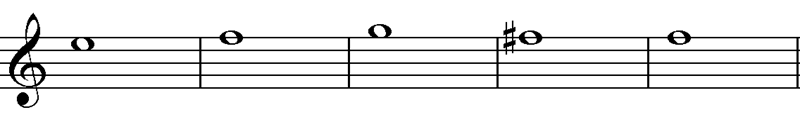

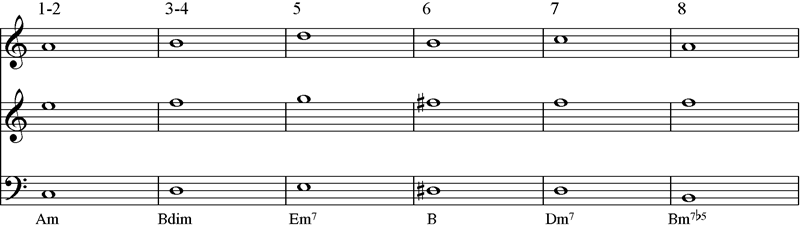

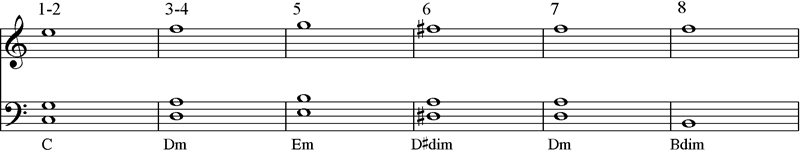

Much of the anaylsis of the individual objects is found in my thesis, so I will just summerize the tonal centers:

Overworld – C

Area Clear – C

Underworld – C

Castle – Minor/Dissonant but loosely G Centric

Level Clear – C (Ending on V)

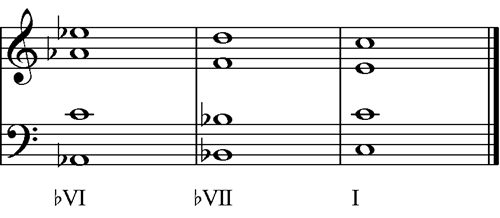

So if you lay out the tonal centers in the linear order of the object, you can see the overall tonal progression from start to finish:

C – C – C – C – C – C – C – C – G – C

While this example is very simplistic, it is interesting to see how every object supports the C tonal center from start to finish until you get to the penultimate object, the castle. The game score moves us to a tonal center on the dominant, which fights for the resolution, just as this level is one of the more challenging of the World, and the most tense. The music reinforces the game play and inform the emotions of the player, so that when the level is completed and the Level Clear object plays, we finally get a resolution to C.

However, as we can see, the object that resolves ends in a half cadence, musically carrying us to the next World and its progression. As you can image, this will continue until the game is won and the final Victory object is played, which ends in the most textbook perfect authentic cadence (melody going from re to do, and the bass from V – I).

I will discuss other types of game score forms in futures posts. For now, I hope that this quick overview will help you start to conceptualize the entire game score as an object and give you tools to start working through larger pieces.