By request, I’m going to take a look at the comparison of The Legend of Zelda (NES) and The Legend of Zelda: Links Awakening (NGB).

The Comment was on my previous post: I'd be more interested in hearing your analysis between this and the theme music for The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening. After the cinematic portion, it's the same tune, but it's played differently.

I love this comment, because this is EXACTLY how I got into doing this research. One of my many theoretical interests is the analysis of similar objects within a series of games (see my article on the analysis of Overworld objects in Zelda).

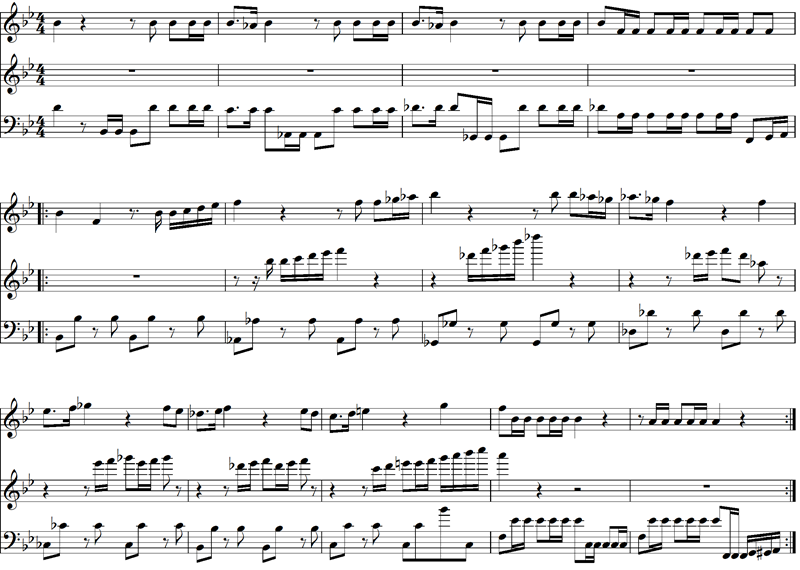

But I digress… lets look at the differences between these two objects. Below is a transcription of the title screen object from The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening.

These two objects are very similar.

To recap from my previous posts, the LoZ title music is structured in the following format:

4 measure intro | 6 measure bridge | 8 measure Phrase A | 12 measure Phrase B

In contrast, the LoZ:LA title music breaks down as follows:

4 measure intro | 8 measure Phrase A + 1 measure extension

It is significantly more compact that the original theme. Harmonically, the tunes are exactly the same. Melodically, the biggest difference is the use of dotted-eight/sixteenth rhythms instead of the familiar triplet pattern.

LoZ:LA lacks a percussion track that was present in the original. It also uses the bass line as two voices, often jumping between registers to provide harmony for the lead track and then a harmonic foundation.

There are little obbligato sections in the middle line that add a different flourish to the tune. The alternating octaves and bouncy eighth-note rhythm of the bass line add a much lighter tone to the object as a whole than the original, which was much more driving and serious.

Some of these differences could be due to space and or sound limitations on the game boy. I find is so interesting that this object completely lacks the triplet figure so associated with many of Zelda’s musical themes across the all the games.

I’m also a very big fan of this one measure extension that was written into the LoZ:LA object. There is no real good reason why they could not have just had the final measure be exactly like it was in the original. Yet, they decided to change the harmony slightly and add a one measure extension to throw us off. The best explanation I can come up for why they chose to do this was to make us think that something different was about to happen. It helps put a period on the object in such a way as to mark the repeat. We are so used to this melody continuing on to a second and longer phrase, but this time it does not, and the change at the end of the phrase defines that point.

So really the biggest difference between these objects is style. Yes the melody is almost the same, the harmonies are exactly the same, yet there are some very interesting differences. Listen two these two objects back to back, specifically listening for the style differences in the way the bass lines are different, as well as the lack of triplet rhythms.